Spotlight: Why your tuition went up, why it will go up again

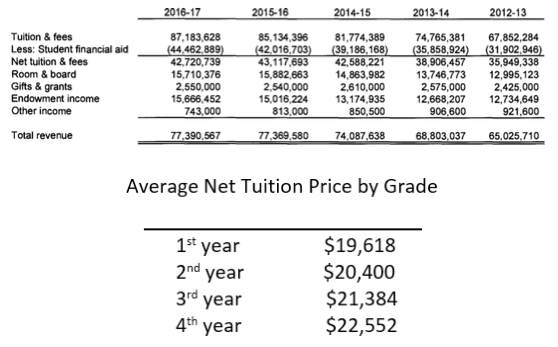

Data courtesy of Vice President Webb

“Costs Rising”: While the price of tution rises, the scholarships earned do not. Each year, students pay more.

October 7, 2016

Rhodes College rolled out a base tuition increase of $2,000 at the end of last semester. While the tuition increase brought revenue to$2,049,232 more than the prior academic year, almost all of it went to funding incoming students’ financial aid, grants and scholarships. Historically, Rhodes has charged upperclassmen students more in net-tuition than first-year students. Thus, the average net tuition price per student increases as students proceed from one class year to the next.

Keep in mind that these tuition statistics are averages and are not indicative of an absolute change in tuition for all students—similarly, financial aid is awarded on a student-by-student basis. However, the gap is clear when comparing that the average senior student paid $22,552 in tuition for a single year while the average first-year student paid $19,618: seniors paid $2,934 more in tuition than their first-year counter-parts. When analyzing the entire Rhodes community, students’ tuition rates increased approximately $1,000 per grade-year.

Rhodes College Vice President for Financial and Business Affairs Kyle Webb said, “every student at the college is charged the same rate of tuition… [However,] the net price for each class increases each year as a result of the annual tuition rate increase. Thus, seniors will have incurred three tuition rate increases during their four years, which typically causes their average net tuition per student to be moderately higher than the average net tuition per student for underclass students.”

After learning about the increases, sophomore Steven Mysiewicz said, “I’m kind of upset. Why would you [increase tuition every year?] Just be straight-forward. Just give us the numbers up front. My family is already struggling to pay.”

Webb emphasized Rhodes has not been engaging in bait-and-switch tactics—a technique called “front-loading.”

“Rhodes does not engage in front-loading of financial aid. Schools that engage in front-loading usually offer large financial aid packages to first-year students as a means of enticing them to enroll and then reduce the financial aid award in subsequent years. Rhodes does not reduce financial aid packages after the first year,” Webb said.

In comparison, Rhodes increases tuition rates over time rather than decreasing aid.

Rhodes is not unique in its tuition revenue processes. Dozens of colleges use this same process or its derivatives. New York University, the University of Arkansas and American University all tend to charge upperclassmen more than lowerclassmen. Regardless, here on campus, several factors—including a decrease in enrollment, inflation in maintenance costs and a newly-hired Title IX coordinator—warranted, if not necessitated, the tuition increase.

“If there were no tuition increase for upper-class students, each first-year student would, on average, have had to pay approximately $5,000 more to achieve the same amount of total revenue,” Webb said.

This, of course, assumes first-year enrollment would mirror that of years past. And, interestingly enough, the newly adopted First-Year Experience was negligible in price—most student clubs costing more in funding.

As to the effectiveness of the tuition increase, Webb said, “Increasing the tuition rate enabled the college to balance its budget without making reductions to academic programs or student services.”